Though it may feel overwhelming, there are environmental education (EE) nonprofits that are reforming adult education, and we can learn from them.

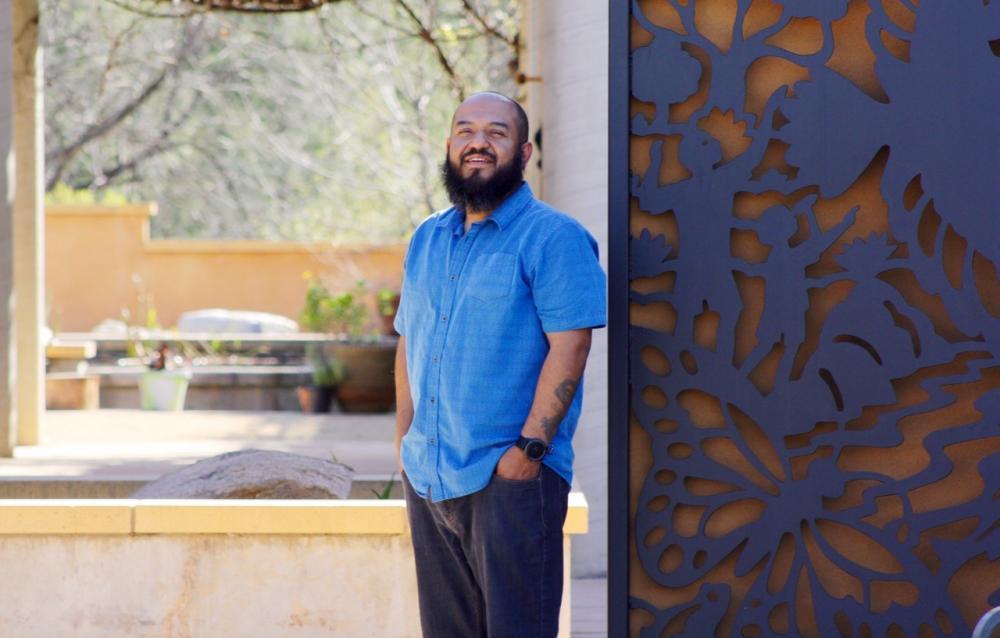

Marcos Trinidad, Center Director of the Audubon Center at Debs Park in LA, has reformed his adult education programs by centering his community’s experience, which is also his own experience. He was born and raised in Highland Park, where the Debs Center is located. His grandmother still lives half a block from the Center and his parents met one block away. The staff he hires not only works with the community; they ARE the community. They work, play, and live in the same communities of his participants. As the senior leader at his organization, he has made the intentional effort to hire staff who can speak directly to the community, who understand the culture and language of its members:

“It is easier to hire people from the social justice field and teach them conservation issues than it is to hire conservationist and try to teach them social justice issues. You can teach someone to bird in 6 months but it would take me 20 years to teach a birder about social justice.”

When asked why he has tackled reforming his adult education programs, Marcos explains that for him, it’s about family and intergenerational learning: “If you don’t get the adults, you won’t get the kids.”

Marcos is changing what adult education at his Audubon center means by changing how we think about environmentalism. When he hears from funders that the need is to teach his community about recycling and water conservation, he thinks to himself, “who has the largest carbon footprint?” The members of his community have one of the smallest footprints, whereas people living in the more affluent communities are likely to have one of the largest.

In all of his programs, he starts by acknowledging that his community’s footprint is actually much lower than anyone else’s: “You check their fridge and there may be 4 butter containers but only one contains butter…but are they considered environmentalists? When you see a grown man riding his daughter’s bike to Home Depot to get work as a day laborer, is he an environmentalist? Or do we only consider that hipster who’s riding his e-bike an environmentalist?” At his center, he openly acknowledges who is actually living a low-carbon lifestyle, and who can learn from this, which flips the philanthropy-programming dynamic on its head. “We often think of wealthy white people writing checks to support EE needs in poor communities, but they are the ones whose lifestyle created the ecological problems we are facing. We can talk about the birds all we want but if we don’t honestly talk about this, we won’t change anything.”

“We often think of wealthy white people writing checks to support EE needs in poor communities, but they are the ones whose lifestyle created the ecological problems we are facing. We can talk about the birds all we want but if we don’t honestly talk about this, we won’t change anything.”

The current environmental system supports the status quo, and that status quo is filled with bias, exclusion, and harm. But within that same system lies the greatest opportunity for change. And this is where programs like Marcos’ Advocacy Boot Camp came from.:“People of Color (POC) are supporting environmental legislation in greater numbers than whites. It’s also POC legislators who are introducing these policies, and they are doing this for their communities, to provide open space and clean drinking water and land for the people. [My programs] are sharing information with the community to help them advocate for things that are important to them.”

With the adults he teaches, Marcos talks about systemic issues, such as homelessness, domestic violence, substance abuse, affordable housing, all in the same context as birds and conservation. He has been able to show his community how all of these issues that are priorities for them are tied directly to conservation. For example, if someone cannot afford housing, it’s a domino effect to being forced to live in the park, and possibly starting a fire for warmth that can get out of control and affect bird habitat or restoration. The dots are all in a line but they need to be connected by educators working with adult populations.

He addresses conservation threats with this holistic approach: “It doesn’t mean we have to change our missions or become therapists or counselors, but we need to be able to partner in a meaningful way to the folks who are doing this work. We need to support the people who we want to support the birds.”

An indirect benefit of his program reform has come in the form of diversifying his audience. The folks from his community are mostly lower-income Latinx people, but there is a lot of transition happening right now, and more folks with money, both white and POC, are moving in. He sees allies in these new residents: “It is so important that these folks attend these programs so we can work together on these issues. Affluent white and POC allies can speak to their networks in ways that won’t be well received if a POC in poverty says it.”

His programs are also attracting a younger audience in their 20s-40s, which is different than the traditional Audubon participant. He is diversifying his audience by leveraging the change happening in his community and focusing these allies on systems-change, not just individual action: “Every class has a systemic action piece built into it. [For example,] participants leave knowing who their representatives are and how to write a letter about a specific piece of legislation that supports environmental justice.”

“Every class has a systemic action piece built into it. [For example,] participants leave knowing who their representatives are and how to write a letter about a specific piece of legislation that supports environmental justice.”

Marcos uses the conservation platform to help his community heal from the embedded white supremacy that has harmed them. He works to decolonize space to support birds, wildlife, and people: “We restore habitat for our birds and wildlife as well as restore the connection of people back to the land.” His accountability is to his community, and he is able to use the Audubon mission to further that accountability.

That said, Marcos clearly stated that he will not do this work at the expense of his community: “You don’t get to choose which parts of community you work with, like just the birds or just the wildlife. If you want to work with community, you have to work with the whole community. If you try to cut the crusts off the community bread, you will do work at the expense of the community.” This means that there is no “neutral” programming that just focuses on wildlife: if it doesn’t directly address the interconnected community and conservation needs, it will unintentionally support the status quo.

“If you want to work with community, you have to work with the whole community. If you try to cut the crusts off the community bread, you will do work at the expense of the community.”

In regards to changing education for affluent white populations, Marcos is planning to work with this audience in a fee-for-service model (not based on donations or grants) to make changes in their communities. In order for our movement to make change on a significant level, that demographic also needs to engage in collective systems action. That said, it isn’t necessarily a POC educator who needs to deliver that message: “[This educator] needs to be someone who can identify within that community, to be that ally who can talk about their journey towards change in a way that resonates with the affluent community, in order to make changes beyond just signing a check to pay for POC communities to change their lifestyle. We have always considered it okay to ask another adult to make change in their lifestyles as long as they are black and brown and poor, but we’ve never turned this around to affluent white populations.”

As the senior leader in a nonprofit organization, I asked Marcos what he would say to a white CEO in a historically white organization trying to make real change: “The CEO needs to focus on their sphere of influence and control: stand for change by getting board members who understand it, by changing how we talk to white affluent donors at the big galas, etc.” The work cannot just be on the program staff. Each of us needs to leverage the control and influence within our sphere. CEOs can reach a sphere that program staff often can’t. Marcos also emphasizes the importance of adequately resourcing any work we try to do, especially if that involves development of white staff to engage authentically with POC communities and of white senior leaders to narrate this with donors appropriately: “It’s important to understand what is vital to your organization to accomplish its mission. If working within POC communities is vital, you have to make a huge investment to fully understand how much work there is, embrace the process, and support it with the right resources. If your donors don’t appreciate that or understand that, maybe you don’t take their money. You don’t have to take money from everyone. It will mean more to the staff who are dedicating their passion and time to accomplishing this mission if you demonstrate your commitment in this way. It is a long-term investment.”

Finally, Marcos has one last bit of advice for all of us adults: “We need to remain teachable. We don’t have it all figured out. We need to continue to grow.”

And on that note, I offer my sincere appreciation to Marcos for the time he took to participate in this interview and for his hard work reforming adult education. To learn more about Marcos and Debs Audubon, or to support their reformational work, please visit https://debspark.audubon.org/.

Header image and image used in post: courtesy of Marcos Trinidad.

1 thought on “Leader Highlight: Marcos Trinidad, Center Director of the Audubon Center at Debs Park”

Comments are closed.